If you were lucky enough to have been among the select few curious indie-rock fans at the Royal when Interpol made its Vancouver debut at that long-defunct Granville Street venue in 2002, you might very well have been instantly turned into a fan for life. That’s the effect it had on me, at any rate, and I have been lucky enough to interview each member of the band at various points over the years.

Sharp-dressed Antics: The Sartorially Stellar Interpol’s Latest Is A Portrait Of A Band Rising Above Cult Status (2004)

This article originally appeared in The Georgia Straight.

For an indication of how far Interpol has come in the past two years, consider that the New York rock quartet made its Vancouver debut at the Royal back in September of 2002. Those in attendance were mostly scenesters and in-the-know rock critics, and a few were probably just there to see the Organ. Some smack monkey made off with two of the band’s guitars and bassist Carlos D had to boot a cigarette-snatching loogan square in the arse, but the 300 or so people who witnessed Interpol’s edgy performance knew they were on the ground floor of something that could become very big indeed.

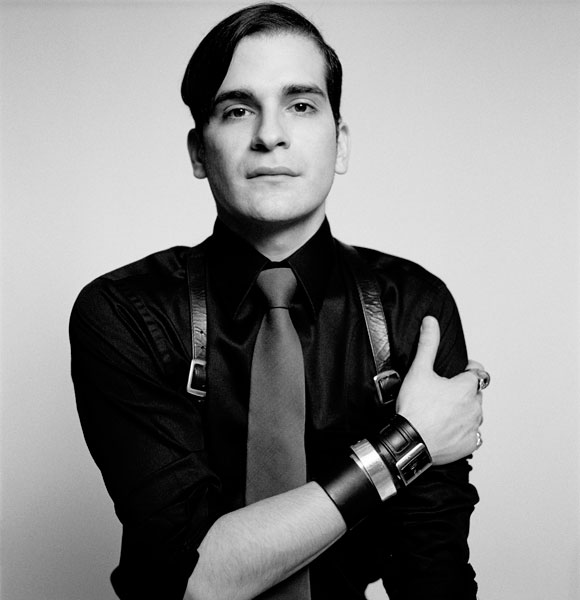

On Saturday (October 23), Interpol returns to our city for the first time since that now-legendary night. This time, the band is playing the Commodore, and the show sold out in less time than it takes to pawn a purloined Telecaster. Clearly, Interpol has become a hot commodity. SPIN magazine’s current issue pegs the ever-dapper Carlos D as the ninth coolest person in music, placing him above such luminaries as Julian Casablancas, Jack White, and Björk. Interpol’s frontman, singer-guitarist Paul Banks, was considered less cool than his bandmate, coming in at No. 29. Still, that’s not half-bad for a guy who, after the release of the group’s 2002 debut, Turn on the Bright Lights, was dismissed by some as an Ian Curtis clone. True, Interpol—which also includes guitarist Daniel Kessler and drummer Sam Fogarino—stakes out a dark patch of turf on the rock ‘n’ roll landscape, and Banks’s portentous delivery added to the calculated postpunk gloom of tracks such as “PDA” and “NYC”. Even so, the barrage of Joy Division comparisons didn’t quite hit the mark and soon grew tiresome.

“People always want to put some kind of category around music. But I feel like the longer that we exist as a band, the more people hear our music, the less we’ll get that kind of shit,” Banks says on the phone from a Toronto hotel room. “Before the first album came out, we’d never dealt with anything like that, so it was like, ‘Whoa, what the fuck? You think we sound like that? Weird.’ You know, I thought we just sounded like us. So it was a challenge to get used to those sorts of things. But I used to say back then, ‘I just can’t wait until we have a new record out, because then people will start talking about the second one versus the first, rather than our only album compared to other bands.’ In a way, you can’t blame anyone. If you only have one record, they can’t compare it to your other work.”

The new one is called Antics, and it’s a step forward for Interpol. The band’s taste for burning-from-the-inside guitar atmospherics and death-disco bass grooves remains intact, but these songs are leaner and tighter, unencumbered by the convoluted arrangements featured on Turn on the Bright Lights. A few of the new disc’s standout tracks, such as the droning, EBow-enriched “Take You on a Cruise” and the storming “Slow Hands” even boast honest-to-God sing-along refrains.

“We wrote in more traditional pop structure on a couple of songs on this album,” Banks says. “There’s more than one song either with no chorus or just one chorus–which you can’t even call a chorus, I guess, if there’s just one–on the first album. We did do a lot of kind of strange structures. And on this one I think we did kind of playfully want to indulge a little more of a pop format on a couple of songs.”

Banks’s voice, too, has undergone a transformation befitting the band’s newfound accessibility. As evidenced by his nuanced performances on “Not Even Jail” and the superbly titled “Public Pervert”, the singer has expanded his dynamic range considerably, a fact he attributes to the amount of time Interpol has spent on the road. “I think if you do anything every day for 16 months, you get better at it,” he offers. “I never really looked at myself as a singer. I was more like the guy with the lyrics in the band, so I would sing ’em. But I definitely became a better singer, just from playing so much. And there’s an awareness, when you’re a little better at something, of how you can use the improvements to broaden whatever it is that you do.”

Interpol’s audience has broadened a lot in recent months. The four-piece spent part of its summer touring with the Cure as part of the Curiosa festival, no doubt winning a few new black-clad followers at every stop. And in the month following the release of Antics, Interpol has garnered more press than most of its Matador Records label mates get in a year. Banks is grateful for the attention, but he says he isn’t quite certain why his band has struck such a resonant chord with rock fans.

“I don’t know,” he says. “I feel great about it, and I think it’s good, because we never compromised. We always did things that we found challenging and kind of compelling musically, and we’ve done the same with this album. I was committed to having shitty jobs for the rest of my life and staying in a band, because playing music is more like a function of your life rather than a legitimate career idea. So I feel very happy and privileged that we’ve had the success that we’ve had.”

Something tells me that Banks, who ended his employment at a café when Interpol started gathering steam, won’t find himself taking orders for low-fat soy lattes again anytime soon.

In + Out: Paul Banks sounds off on the things enquiring minds want to know

On the fact that Internet music pirates were downloading and trading Antics months before its official release: “It was just unfortunate, because I like the tradition of release dates. There’s something to be said for keeping the integrity of a convention like a release date and the excitement that a kid might have, like, ‘I can’t wait till this day.’ But as far as people downloading it, how can you complain? It’s enthusiasm for the music at the bottom. I think everyone’s just got to figure out how to keep the industry afloat with downloading, and it will be figured out at some point. It didn’t bother me, because, as I say, it’s just people who want to hear the music, so how are you gonna get pissy about that?”

On not holding a grudge against Vancouver, where he and Daniel Kessler had guitars stolen two years ago: “It was one junkie. It wasn’t Vancouver that stole our shit. It was just a really unfortunate thing. But I got my guitar back weeks and weeks later. The unfortunate thing is Daniel, who had spent a lot of time finding his guitar, never got his back. It’s definitely not a great memory, but what are you gonna do?”

Interpol man loves to score (2008)

This article originally appeared in The Georgia Straight.

Backlash can happen to the nicest people. Case in point: Interpol’s most recent album, Our Love to Admire, is the New York band’s highest-charting and biggest-selling effort to date, but its release last July was given the cold shoulder by certain hipper-than-thou blogs and on-line arbiters of indie cool.

Stylus gave the record a grade of D, while Pitchfork’s review characterized the disc as bloated and self-indulgent. Reached at a tour stop in Barcelona, Spain, Interpol bassist Carlos Dengler laughs off the latter critique.

“They’ve always been on our side, as well,” he says with a gasp of mock-horror. “They defected! We were so hurt!”

The unerringly charming Dengler continues: “It is exceptionally elementary for me to filter out all that sort of noise. When you really try to do something from a place that is based on love and artistic integrity, these questions of whether this is good enough or not, of whether this meets this expectation or that—these questions become so shallow and so hollow.

“Because what you’re really connected to is something that those questions are not even tapping into, which is the expression of your artistic self, and the fact that that is being honestly portrayed.”

In any case, Our Love to Admire—Interpol’s Capitol Records debut after two albums and three EPs with Matador—speaks for itself. Where 2002’s Turn on the Bright Lights burned with spare, edgy post-postpunk, and 2004’s Antics upped the ante with mammoth choruses and indelible hooks, the latest disc finds the group at its most lush.

Produced by Rich Costey (whose previous clients include Franz Ferdinand, Muse, and Mew), Our Love to Admire boasts a clean but layered sound, with songs such as the opening “Pioneer to the Falls” brimming with carefully orchestrated keyboard parts.

That would be Dengler’s doing. On tour, he leaves the keyboard duties to Frederic Blasco, but in the studio the bassist does it all himself. Usually, the addition of keyboards to an Interpol record is something of an afterthought, but this time around, Dengler’s compositional contributions were conceived as an integral part of the album’s sound.

“I guess I found myself exploring avenues that I didn’t really foresee myself exploring when I joined the group,” he says. “There was some apprehension on my part in terms of introducing these new influences, but they seemed to work really well right off the bat when I introduced them in the rehearsal space when writing the songs for Our Love to Admire. That was really reassuring to me, so I kept going with it and have not stopped since then.”

Dengler, who says he listens only to classical music and has been taking composition classes, sees a future for himself in creating film scores. He cites other rockers-turned-composers such as Danny Elfman, Hans Zimmer, and James Newton Howard as inspirations. On his website, the musician has posted some of his works to date, including an orchestral mix of “Pioneer to the Falls” and a short film called “Golgotha”, which he scored and created with director Daniel Ryan.

“It’s me in front of a computer,” Dengler says of his compositional setup. “Actually, I have a huge guilt complex about using orchestral samples as opposed to the real thing. Unfortunately, I’m in no position to request the usage of a full symphony orchestra.”

Well, not yet, anyway. That should give the man something to strive toward. In the immediate future, Interpol has a date with the Pemberton Festival, which will mark the official closure of the Our Love to Admire tour. Local fans heading up the Sea-to-Sky Highway for that will probably want an update about Dengler’s current look.

After all, the guy is known for always sporting a characteristic image. When Interpol first came to prominence, the bassist—then known as Carlos D.—often rocked a sleek gothic storm-trooper style, complete with Hitler bangs and a none-more-black wardrobe. Last year, he set off a newly grown mustache-and-soul-patch combo with a bolo tie, for an effect that was part classics prof and part Col. Sanders. In a cool way.

So what, pray tell, is Dengler’s look for the current tour? He’s surprisingly reticent to say. “For me to really answer that question would be, in a way, sort of validating the notion that I am planning these things in advance,” he says, cautiously. “And I’m not so comfortable with validating that notion.”

After a little prodding, the indie icon admits that he has given a lot of thought to his appearance and how it shapes the public’s perception of him as an artist.

“Just for the record, I realize that the pop genre specifically, with its preoccupation with celebrity-obsession culture and fame, and idolization of the hero on the stage that is supposed to be somehow all-powerful and communicate the musical message—this is obviously an addiction that is cultivated and fed by the industry, which itself is commodity-driven,” he says.

“It’s built into this genre that there is a style that needs to be expressed visually, and on your actual physical person. I’ve always known that and I’ve always exploited it. I feel that it is part of my artistic process, actually, to do that. And it’s also part of my artistic right, if you will, to fluctuate and do whatever I want with it whenever I want—and to not have to account for it ever.”

That’s all well and good, but it doesn’t tell us what he’s going to be wearing, which is what enquiring minds want to know. Pretty please?

“Because you’re being so insistent,” Dengler says, “let’s just say that I think right now, especially since it’s the end of the tour and I’ve got my sights set on things that are happening after, a certain distinct or robustly communicable image is not exactly on the highest rung of the ladder of priorities.”

Rest assured, though, that the alt-rock sex symbol will look way cooler than you—even if he’s not trying.

Interpol charts a new course (2011)

This article originally appeared in The Georgia Straight.

Meg Wilhoite likes Interpol. That’s not unusual; after all, the New York–based band has developed a healthy following since releasing its first long-player, Turn On the Bright Lights, in 2002. Wilhoite’s interest in Interpol, however, borders on the obsessive. Since 2007, she has operated a blog called Music Theory & Interpol, on which she posts detailed analyses of the group’s songs. As of this writing, her latest upload is a nine-minute video dissecting “Always Malaise (The Man I Am)”. Wilhoite’s crowning achievement, however, is her in-depth essay on “NARC”, which is just over 1,500 words long and describes the track’s progression through the aeolian and phrygian modes.

According to Wilhoite, Interpol’s music is distinguished by its unorthodox use of polyphony and counterpoint, but what makes it truly addictive, she writes, is that it “influences a fusion of intellect and sensuality in us as listeners”.

The existence of Wilhoite’s WordPress page is news to Daniel Kessler, and it elicits a chuckle when the Straight reaches the Interpol guitarist in Milan, Italy, where he’s enjoying a short break from touring. “That’s pretty funny—and flattering, I would think—that somebody has a blog called Music Theory & Interpol,” he says. “It’s not surprising to me, based on how our band writes songs, that there are quite a few things that are a bit unconventional, just by the nature of who we are as individuals and the nature of how the songs come to be at times, and what we bring to each song and so forth.”

It’s Kessler himself who has always generated most of the band’s musical ideas, and last year’s eponymous Interpol was no exception. Often in collaboration with since-departed bassist Carlos Dengler, the guitarist came up with the songs’ basic templates, to which drummer Sam Fogarino and singer-guitarist-lyricist Paul Banks then added their contributions.

Carrying on in the vein of 2007’s Our Love to Admire, which took a step away from the spare postpunk of the quartet’s debut, Interpol is a sonically rich affair, brimming with harmonic layers and well-thought-out arrangements. Kessler says that in the past, things such as keyboards were afterthoughts, window-dressing added on after the songs were written. This time, though, they were conceived as integral parts of the compositions, and indeed it would be hard to imagine “Summer Well” or “Try It On” without the insistent piano parts that propel them. Kessler says this approach helped set the band on “a new trajectory”.

It doesn’t hurt that the songs are driven by one of the most accomplished rhythm sections in indie rock. “Success”, for example, opens the album with ferocious kick drum and bass guitar that sound telepathically linked, while “Memory Serves” lopes along to a stuttering, bottom-heavy shuffle that might well have turned disastrous in the hands of players less skilled than Dengler and Fogarino.

Kessler gives the drummer top marks for his eagerness to explore new ways of creating beats. “Even a song like ”’Summer Well’, I think his first instinct when we were writing that was to actually create a bit of a drum loop,” the guitarist notes. “He had that in place early on in the writing process of that song. That’s one of the songs Carlos and I got together with, and one of the first songs we started working on as a band. We did a demo of that song early on, so I think that helped give Sam a bit of time to think about it, but then by the first couple of rehearsals with all of us in the room, he brought forth this drum loop, and he played on top of it very much in the manner that it is on the record. I think that was sort of telling of where he was at as a musician, and also it was very much in sync with where I’m at as a musician. I just liked the fact that it was quite minimal, but then it was adding something quite different and really sticking out. And the way we mixed the record, those little rhythmic moments really pop out.”

Given the striking tightness of Interpol’s rhythm section, it came as a shock to fans when the band announced last May that its resident four-stringer and fashion icon Dengler had quit to pursue other interests, such as composing film scores and, one would guess, cultivating new and fascinating hairstyles. David Pajo, known for his work with the likes of Slint and Tortoise, is now taking care of bass duties as part of Interpol’s touring configuration (which also includes keyboardist Brandon Curtis)—but as for the future, who knows? Certainly not Kessler.

“In all honesty, we haven’t really spoken about a plan of what we’re going to do as far as how we’re going to go about writing once this campaign winds down,” he admits. “But that’s not really surprising to me, because we’ve never been a band that’s really made plans beyond the immediate future. During Our Love to Admire we never made a plan for how or when we were going to go about writing, and after Antics we never really made that plan either. We got off the road, got a bit of perspective, and then figured out when we were going to tend to the next album. So, to me, that’s just sort of par for the course.

“I know there’s probably a lot of questions and a lot of things to think about, but sometimes it feels quite healthy to live in the now, in the moment,” the guitarist concludes. “We have a lot of great things lined up, and we’re going to be pretty busy for the most part of this year, so I think we’ll figure that out in due time, like all things.”

Interpol confidently redefines its bottom line (2014)

This article originally appeared in The Georgia Straight.

Let’s go ahead and call it a comeback. Interpol never actually broke up, but the New York–based band did take a hiatus after the tour in support of its self-titled fourth album.

That arguably underrated 2010 release was the group’s least successful, but “success” is relative: despite suffering in comparison to what had come before it, Interpol still landed in the Billboard Top 10 and garnered some positive reviews.

Nonetheless, the band had a good reason for taking some time off: after completing work on Interpol, founding member Carlos Dengler packed up his black Fender Jazz Bass and his empty shoulder holster and took his leave. His erstwhile bandmates hit the road without him, and then went their separate ways. Singer-guitarist Paul Banks focused on his already-extant solo career; drummer Sam Fogarino picked up a six-string to front a new project called EmptyMansions, which also featured Interpol’s long-time touring keyboardist, Brandon Curtis. And guitarist Daniel Kessler? Well, it turns out he was working on new Interpol songs.

Speaking to the Straight from Athens, Georgia, which he has called home since 2008, Fogarino recalls that the three remaining members reconvened at the behest of Kessler, who, true to his nature, stopped short of explicitly suggesting the band make a new record.

“He’s always been the instigator of all things Interpol, in terms of the songs,” Fogarino says. “He’s so noncommittal, and keeps his cards close: ‘Maybe we should get together.’ There was a break. It was 2012, and Paul was doing his solo record [Banks]. I think it was just before it was going to be released. He had finished recording it, and there was a window of time just to play around with some ideas. It was totally Daniel just seeing what Paul was up to, and then he gave me a call and said, ‘You want to come up to New York for a week?’ ”

The three men tossed some ideas around, reignited their creative spark, and then started writing a new album in earnest at the start of 2013. As to the question of who would step into Dengler’s combat boots, well, it practically answered itself.

“Paul realized that, the way the band had worked, it was always with bass lines already written when he would approach the songs guitarwise or from a vocal standpoint,” Fogarino notes. “And he realized that he had to kind of take it upon himself.”

Banks ended up writing and playing all the bass parts for the just-released El Pintor. (The title is Spanish for “the painter”, but it’s also an anagram of the group’s name.) Fogarino says Banks turned out to be “a natural”, noting that the frontman lived up to the seemingly impossibly high standard set by Dengler, whose distinctive playing had been one of Interpol’s defining characteristics.

“You’ve got to face up to it: Carlos was an excellent bass player, and we can’t all of a sudden start playing root notes now because he’s gone,” the drummer says. “But Paul’s a very well-rounded musician and a really good songwriter, and I think that’s what we all relied on when it was the three of us, that we all kind of pull from our ability—or at least our passion for songwriting, and for songs.”

Banks proves his mettle early on El Pintor. After a few deceptively serene bars, the opening track, “All the Rage Back Home”, explodes into a pulse-quickening groove built around a gritty four-string line and one of Fogarino’s most propulsively demolishing beats. The song’s immediacy and its instant-earworm chorus stand in marked contrast to much of the material found on Interpol, which was emotionally stark and relied more on brooding, 2-in-the-morning ambiance than on hooks.

El Pintor is hardly devoid of such atmosphere; “Tidal Wave”, for example, has enough melodic melodrama to please the most discerning postpunk punters, especially when Banks intones the portentous lyric “There’s a flood coming soon.” The song is enlivened and carried along by Fogarino’s rolling-thunder beat, however, and that’s one of the keys to the success of the record, which has been hailed as a return to the form Interpol showed on its first two long-players, 2002’s Turn on the Bright Lights and 2004’s Antics. The songs might explore cold, dark corners, but the band itself is clearly on fire.

“It seems like we were able to keep the tempo more upbeat while still being a little introspective—or moody, for lack of a better term—on this record,” Fogarino concurs, although he notes that he might have taken things into a wholly different realm, rhythmically speaking, had it not been for the encouragement of his bandmates. “There were a couple of points with some of the songs—‘Same Town, New Story’ and ‘Twice as Hard’—where I didn’t even want to put drums down. These melodies were just so rich and beautiful and cinematic, and it took me a minute to kind of feel that I was safe, that I wasn’t going to taint them with, like, a rock beat, you know? But as soon as you catch Daniel and/or Paul’s attention with something, they’re not gonna let it go. So as soon as I played something, it kind of took the song in a different direction. And I was still kind of like, ‘Oh, am I pissing on this?’ You know, ‘Does it need to do this?’ And they were like, ‘Yes.’ There was this underlying excitement to what was going on. I think sometimes you strike a balance, where you can have something a little more mature, but still kind of driving at the same time.”

Mind you, there was never any real danger that the endlessly inventive drummer would simply tap out a standard four-on-the-floor rock beat.

“I couldn’t if I tried,” he admits. “I just have this weird self-taught angle that I come from. Sometimes when I think I’m being really straight and to-the-point, people tell me otherwise. It can be frustrating sometimes—then again, I’d probably be bored just laying down a template.”

Debauchery behind it, Interpol still thriving as the band heads to vancouver (2019)

This article originally appeared in The Georgia Straight.

It’s a striking photograph: a long shot of a man in a suit seated alone at a table flanked by potted plants, an array of microphones in front of him and tape recorders on the floor. The image, which adorns the front cover of Interpol’s latest album, Marauder, is legendary photog Garry Winogrand’s shot of a press conference by former U.S. attorney general Elliot Richardson, who in October 1973 announced that he would resign from his post rather than obey President Richard Nixon’s order to fire Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox.

It’s a picture of a moment that resonates powerfully in the present day, when the United States can only hope for someone with Richardson’s resolve to stand up against a corrupt administration. When the Straight reaches Interpol’s Sam Fogarino at his home in rural Georgia, the drummer says that harking back to the Watergate era was, in part, a way of reflecting on contemporary America.

“It was, inadvertently,” he says. “Because we initially just saw it as an image. Of course, there’s no way that current events can’t resonate when you see that photograph. You don’t have to know anything about it, but something serious is going down. In this grand era of the apology, of coming forward, it seems as if this person has something really awful to reveal about himself. The beautiful thing is that he was the good guy. He was the one who said ‘Fuck this. I’m not going to be a criminal for you. I’m out.’ ”

No one would ever mistake Marauder for a Rage Against the Machine record, mind you. Winogrand’s photograph was no doubt chosen more for its evocative visual qualities than for its content; Interpol has always avoided making obvious political statements. The band’s sixth LP deals less with what’s happening in Washington than with what’s going on inside the mind of singer-lyricist Paul Banks. As usual, Banks’s songwriting is hard to parse, but his weary baritone implies regret at roads taken and wistful agonizing over those untrodden.

Musically, the record, which the band recorded with producer Dave Fridmann (Mercury Rev, Flaming Lips) at his Tarbox Road Studios in upstate New York, expands upon Interpol’s signature palette of early-’00s indie rock and jet-black postpunk. The focal point is the interplay between the guitars of Banks and the band’s main composer, Daniel Kessler, but on the rhythmic end of things, Fogarino peppers his solidly propulsive drumming with beats that swing in unexpected ways.

Since the departure of bassist Carlos Dengler in 2010, four-string duties in Interpol have been divided between Brad Truax, who holds down the bottom end on tour, and Banks, who does so in the studio. Fogarino says he and the frontman make such a potent rhythm section because “We just understand each other. The thing that really works—for my ego, to be blunt about it—is that he loves what I do behind a drum kit. He values my sensibilities and always tries to figure out what I’m doing and translate that on the bass. He’ll hear stuff I’m doing that I don’t hear and lock into it. It’s exciting, even at this point in the game, because he has an invigorated approach to nailing some bass lines.”

That Interpol is still going, let alone thriving, in 2019, is impressive in itself. Along with the Strokes and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, the band rose out of the fabled NYC music scene at the turn of the century, a milieu documented by Lizzy Goodman in her book Meet Me in the Bathroom: Rebirth and Rock and Roll in New York City 2001-2011. Certain members of Interpol had a serious taste for debauchery in the group’s early years. When things got especially decadent around the time of Interpol’s second album, 2004’s Antics, Fogarino—a full decade older than Banks and reputedly the most mature member of the crew—almost reached his breaking point. Goodman quotes the drummer as saying “Mentally, I was quitting the band every week.”

Fogarino opted to stick with the group, although he did eventually pull up stakes and relocate to Athens, Georgia. He has since moved to nearby Winterville—a small town best known to alt-rock cognoscenti as the onetime home of the Butthole Surfers.

“Around the Our Love to Admire period, I just decided that I wanted to get out of the city and have more space,” he recalls. “There was no real fear of losing the New York edge, because the band was still based there and ultimately I’d be travelling back and forth. Now I have a kind of duality. There’s Interpol life and there’s home in Winterville, which is definitely a contrast.”

As for those chaotic early days, he has no regrets. “That time was awesome,” he admits. “But would I want to be doing that now, at 50? I don’t think so. But you get to revisit that on tour. There’s ultimately moments where we’re all stuck together, and thankfully we still like each other. So everybody can make one another laugh at any given time—or really angry. So we still have that little gang mentality, if you will, like ‘The rest of the world does what they do, but we do this.’ That little bit of us-against-the-world, romantic rock-star notion.”

That mentality should serve Fogarino well in 2019. He’ll be spending much of it on the road in the company of Banks, Kessler, Truax, and longtime Interpol touring keyboardist Brandon Curtis. Fogarino confesses that he doesn’t always love touring, which is a life that can breed homesickness and exhaustion. What he does love, on the other hand, is playing his drums for an appreciative audience night after night.

“What’s never work is performing,” he says. “But there’s the downtime, away from home, that can sometimes make you go, ‘What am I doing? I’m in the middle of nowhere.’ And you don’t want to go to a museum or an art gallery, you just want to be at home. But then on the other side of it, you get to travel the world playing your music for people, and then you get a couple of years off. So it all balances out.”

Leave a comment